The Recent Past

Remember the great recession of 2008? Well, after almost a decade of supporting the securities markets (stocks and bonds) with independent monetary policies the Federal Reserve acknowledged that it was time to add fiscal policy. There were signs things were beginning to perk up after the Trump administration passed the (TCJA) Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which took effect from December 31, 2017, through January 1, 2020. Then, however, Covid-19 hit and every form of added fiscal spending was considered.

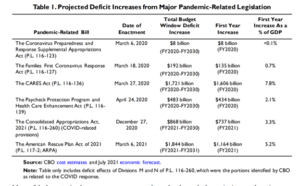

The Federal Reserve Board had long known that sometimes the use of monetary policy alone is not enough to reinvigorate an economy. Sometimes you need to engage both monetary and fiscal policy simultaneously. So, when the sudden and severe decline in activity (from lockdowns) caused the national unemployment rate to rise from 3.5% in February of 2020 to 14.7% in April of 2020, the highest monthly rate ever recorded, Congress was willing to add fiscal stimulus to monetary stimulus. The Congressional Research Service states that “Fiscal stimulus is short-term spending increases or tax decreases designed to increase short-run economic output. According to theory and historical evidence, fiscal stimulus can reduce the decline in output and employment associated with recessions….”

Future Considerations and Inflation

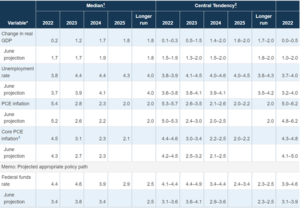

As to future considerations, While the Congress and the Senate are both strictly controlled by the Democrats, “no consensus exists in the economic or policy community regarding how long or how much stimulus is appropriate…” The emphasis of uncertainty focused on problem solving rather than creating future problems. As we now know congressional fiscal and monetary strategy created both. It buoyed an economy shutdown by law makers and pumped so much money into the U.S. economy the result is the highest inflation rate in decades. Other economists are concerned about the growing and historically large debt-to-GDP ratio. Inflation has been relatively high since March of 2021. The Federal Reserve thought inflation would decrease back to 2.1% by 2022. They were wrong and now must fight inflation over a multi-year plan as engaging in too much slowing too quickly would take the U.S. economy back into recession, which in turn would require more monetary and fiscal stimulus. Using rate hikes to slow the economy as shown below is the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Systems expected time frame to tame inflation and with it the volatility experienced in the stock and bond markets thus far in 2022. Note the change in real GDP growth from 2022 to 2025. Also, the rise in the unemployment rate in 2023 and 2024 and the Federal funds rate for 2022 and 2024.

This year, real GDP growth has been negative for two quarters in a row and the third-quarter estimate from the Atlanta Fed’s GDP now indicates sluggish growth of only 0.3%. Real growth reports have been mixed—with employment strong while housing activity collapses—but overall, real economic growth has slowed markedly and, currently, is modest at best.

Currently the inflation rate is certainly high by historical standards, but it has clearly peaked. Moreover, evidence across a wide variety of measures—commodity prices, wage inflation, most core inflation gauges, import prices, tech prices, vehicle prices, trucking and shipping rates, and retail price discounts due to high and rising inventories— imply that inflation is decelerating. In addition, inflation expectations are hardly becoming embedded. Pricing in the housing market is falling sharply. That’s good news since the investment community has recently been caught up in fear of inflation (which lowers asset values, both stocks and bonds) and fear that since the Federal Reserve was initially wrong about the stickiness of inflation it will continue to raise the cost of borrowing in order to squash the belief in future fiscal and monetary supports. People must learn inflation is dead, dead, dead. Dead. That’s what the Fed wants. And because their plan is working, please review the chart above which shows that for every year inflation declines (2022-2025) they see GDP reaccelerating. So, the future is bright. We just have to deal with the pain that gets us to the second quarter of 2023. It would seem the Fed doesn’t really need to keep raising the funds rate at this point. Growth in the money supply has disintegrated, fiscal deficit spending to GDP has fallen significantly, the dollar has surged, and yields are up across the curve. Due to the lag effect of the high cost of borrowing-which causes inflation to ease, an acceptable level of inflation should be in place by the spring of 2023.

Implications For Stock Investors

The Fed is an independent body composed of smart people, and as it has demonstrated, can do what it believes is best. Of course, there is a risk when you ignore your bosses and go rogue. It is particularly precarious when decisions are divorced from free-market price discovery. How does the Fed know that 4%, 4.5%, or 5% is the correct level for the funds rate? For months, the 10-year bond yield seemed pretty content near 3.5% until the Fed kept pushing the funds rate higher with promises of more to come.

Paul Volcker did the same thing “briefly” in the early 1980s. Despite a deceleration in annual CPI inflation, Volcker ignored bond pricing and forged his own path. However, his 15 minutes of fame was implemented after 15 years of runaway inflationary pressures. The contemporary Fed is following its inner-Volcker after just 15 months of elevated inflation. For investors, whether the Fed is right or wrong is a moot point. Even though this is not the end of a prolonged secular-inflationary cycle, similar to the 1970s, because the Fed has seemingly decided to mimic Volcker’s historic moment, investors need to consider what this aggressive action implies for the stock market.

First, it’s still possible that economic reports will worsen (real growth) or improve (inflation) enough to convince the Fed to pause. A big drop in headline CPI? A bad jobs number or a rise in the unemployment rate? For stock investors, any hint that the Fed may soon pause (or maybe even an inkling that it’s considering smaller rate hikes) would probably be met by a rip-roaring rally. That would be the soft-landing scenario. Given the Fed’s ardently expressed mission, however, it seems unlikely that will happen before year-end and before the Fed does more damage.

Second, during a tightening cycle, what frequently happens is something “breaks.” It doesn’t have to be a U.S.-centric problem. For example, the 1997 Asian crisis and the 1998 Russian debacle were both non-systemic crises. Perhaps, Europe blows, or China? Except for China, global policy officials are now pressuring the economic system in a unified fashion. Such events tend to be sharp but short-lived and any stock market selloff is often regained quickly. The good news here for investors is any short-term crisis would likely pause Fed tightening, and since the stock market is already off significantly, it may not have much additional or lasting negative impact. Indeed, in a perverse fashion, a non-systemic “crisis” could prove to be a positive for stocks.

Third, is the hard-landing scenario: a recession. The longer and more aggressively the Fed tightens, the more likely that outcome. However, the hard-landing odds would rise substantially if the Fed lifted the funds rate above the 10-year Treasury yield (i.e., invert the yield curve) and kept it there for a few months. What would an imminent recession mean for stocks?

A deep and protracted recession would almost certainly force the stock market lower. If it destroyed earnings and/or was accompanied by a burgeoning credit crisis, this year’s downside, so far, may simply be a warm-up like 2000 and 2008.

However, in our contemporary situation, the stock market is already down by a large amount. This year, the S&P 500 declined steadily even before the Fed began increasing the funds rate. That was not the case in many past bear markets. For example, in the late 1990s, the Fed began raising the funds rate in June 1999 and did not stop until May 2000. Nonetheless, in September 2000 the S&P 500 was still virtually at a record high, unlike today. That is, the early 2000s bear market did not even begin until after the Fed stopped lifting rates. By contrast, while the Fed is still increasing rates today, the S&P 500 is already off about 25% from its record high. In the aftermath of the 2000 dot-com peak, the bear market didn’t drop by 25% until March 2001 and was still off by only 25% in April 2002. That is, stocks have already seemingly discounted higher yields much more at this point than in 2000.

The same story can be told about the 2007 market crash. The Fed began tightening in July 2004 and stopped in July 2006 after raising the funds rate by 4%. However, the S&P 500 just kept rising and ultimately peaked in October 2007—long after the Fed had stopped boosting rates. Again, today, the stock market is already off by 25% yet the Fed is supposedly not even done tightening. By comparison, during the Great Financial Crisis, it took until September 2008 for the S&P 500 to be down 25%. How much more downside could still exist (even if a recession occurs) when, unlike in 2000 and 2007, stocks have already collapsed significantly?

Maybe the most illuminating example comes from the Volcker era: When Paul Volcker went rogue with rate hikes in 1980 to kill inflation, the S&P 500 did not even start to decline until the funds rate reached its terminal level. Volcker began to increase the funds rate in August 1980 and by December 1980 had lifted it from 9.5% to its peak of 20%. The S&P 500 topped at about the same time the funds rate reached 20%. The ensuing bear market, which ultimately bottomed in August 1982, declined in total by just 27%. Has today’s stock market by now discounted additional Fed tightening and a recession? In 2022, at a similar point as 2000, 2007, and even the 1980’s “Volcker moment,” the S&P 500 has already plunged considerably more.

Finally, there are notable recessions that were preceded by stock declines that never reached the bear market threshold. For example, the S&P 500 dropped 14.8% ahead of both the 1953-54 and 1957-58 recessions. It fell only 13.6% leading up to the 1960-61 recession and was down by just 19.9% prior to the 1990-91 recession. Obviously, an imminent recession does not necessarily guarantee the contemporary bear market will fall much further than it already has.

Recessionary Characteristics Already in Place

There are several noteworthy characteristics evident now that are reminiscent of the end of a recession rather than the beginning. In our view, those characteristics could help moderate both the magnitude and the duration of any pending recession.

First, the balance sheets of households and corporate sectors are remarkably healthy based on key metrics, like debt-to-income ratios, debt/service ratios, and liquidity levels. Normally during an economic expansion, balance sheets become extended and vulnerable because animal-spirit behaviors lead to excessive spending and borrowing. That has not happened in the post-pandemic recovery as confidence has remained remarkably subdued. The household debt to personal income ratio is as low as the early 2000s and not much above the level of the early 1990s. Moreover, despite this year’s rise in yields, the household debt/service ratio is still less than at any time prior to the pandemic. Likewise, the ratio of U.S. corporate debt to after-tax profits is as low today as it was in the 1960s. Usually, at the end of a recovery, private-sector balance sheets look abused and suspect. By contrast, at present, they resemble how they appear at the end of a recession—after they have been cleansed and re-liquified.

Second, although many post-war recessions were made worse by a banking crisis, the U.S. banking industry is currently squeaky-clean. Tough legislation surrounding banking rules after the 2008 financial crisis practically mandated banking virility. Consequently, unlike in the past, a recession should not expose banks swimming without their suits.

Third, private-sector confidence has never been as depressed outside of a recession as it is today. Despite an ongoing economic expansion, U.S. consumer confidence has only marginally lifted from all-time lows. Similarly, measures of CEO and small-business confidence have seldom been weaker. Indeed, I cannot remember another time when so many CEOs expected a recession while still in a recovery. Historically, one of the primary factors aggravating recessionary contractions was a breakdown of private-player confidence. As confidence turns to fear in a recession, animal spirits are vanquished, extending and deepening any recession.

For example, in 2000, the U.S. Consumer Sentiment Index was at a record high above 110 and it declined by almost 35 points during the ensuing recession. Likewise, that index peaked at around 100 in 2007 and collapsed to 55 by late 2008. Today, however, the index was at a record low of 50 (in June) and is still below 60. Perversely, the U.S. may be headed into a recession at a time when confidence among both consumers and businesses—after being ravaged by surging inflation—is just now starting to turn up. Consequently, a recession could prove abnormally modest, mainly because confidence can’t fall much further and may be contrarily improving just as a recession commences.

Fourth, liquidity and dry powder are noticeably abundant. Often, recessions develop because financial liquidity becomes strained, and savings evaporate. Indeed, recessions are normally required to re-liquify players and give everyone a chance to replenish savings. Today, though, by some estimates, households still have almost $2 trillion in excess savings accumulated post-pandemic. Because monetary growth has been so extreme in this cycle (a $9 trillion Fed balance sheet), liquidity is uncharacteristically sloshing about everywhere. That may explain why corporate junk spreads are still only slightly above 5% in the face of widespread recession fears (normally junk spreads jump to at least above 8% prior to a recession).

Heading into the 2008 GFC, household cash holdings were only about 2% of total debt holdings. In 2000, cash reserves were less than 5%. In contrast, at present, cash is about 25% of total household debt—the highest level since 1970! Likewise, the U.S. corporate cash flow/GDP ratio is at 13.5%—only slightly below its post-war high of 14% (after the 2008 crisis). Before 2008, the ratio had always been less than 12% and typically slumped below 10% in advance of a recession.

How bad would a looming recession prove to be when so many private-sector players are financially strong, highly liquid, and possess substantial untapped spending power?

Finally, if the economy is headed for a recession, it will do so in a unique fashion because of the pandemic, as the supply side of the economy is still trying to catch up with demand. Oddly, any demand slowdown may cause a smaller contraction in overall economic activity because supply could still be expanding. This is already happening in the labor market: U.S. job growth through August had risen by a 2.7% annualized pace. Yet, over that same period, the unemployment rate barely declined, while wage inflation decelerated. How has such robust job creation not lowered the unemployment rate more and heightened wage pressures? Because the job market has been mainly driven by a “supply-side” revival. The labor force (i.e., labor supply) has grown nearly as strong, at a 2.3% annualized pace. Entering a recession while the labor supply is still recovering from the pandemic is an odd, if not unique situation and should help temper any economic contraction.

Automobiles are another example of how supply-side activity, still recovering from the pandemic, could help limit the negative force of a recession. In the last two recoveries (the early 2000s and post-2009), total U.S. auto sales averaged close to an annualized pace of 17 million. Currently, because of supply restrictions, U.S. auto sales have been limited to an annual rate of just 13 million. Many consumers want to buy a vehicle, but they are simply unavailable. Therefore, a recession may lower total demand for automobiles, but overall sales could still unconventionally rise as supply-side problems recover and mitigate the possibility of a decrease in demand, which is customarily an effect of recession.

If the Federal Reserve maintains its path to higher rates, it may well push the economy into a recession next year. However, the recession could nonetheless prove remarkably mild considering the unusually strong balance sheets, how low confidence already is, the amount of dry powder already on reserve, and how much supply-side activities may continue to improve. A 25% stock market decline may already be sufficiently discounting any pending recession.

Other Mitigating Factors for Stock Investors

In the end, among all the fear and market carnage created by ongoing and aggressive Federal Reserve actions, investors should not lose sight of three important positives for the stock market.

First, “peak inflation” has historically proven to be a good buying opportunity for stocks. From the 17 previous peaks in the CPI inflation rate since 1940, the S&P 500’s average-annualized-forward price gain was 13.2% in the coming year (please see Paulsen’s Perspective June 7, 2022). It was still +8.8% if a recession resulted (which occurred eight of the 17 times) and was +17.2% without a recession. Peak inflation is often associated with improved confidence and peak yields. Indeed, S&P 500 one-year price gains following the three major inflationary tops of the 1970s-80s (February 1970, November 1974, and March 1980) were, respectively, +8.1%, +30.4%, and +33.2%! Those “post-inflation-peak” returns were earned despite a recession occurring in each case.

Second, like Main Street, Wall Street confidence is depressed. Investor sentiment measures are suggesting extreme pessimism and potentially washed-out selling. Nervous Nellies have had ample opportunities to sell out this year. How many sellers are still left? The CNN Fear & Greed Index is currently at 19—an “extreme fear” reading. The AAII Bulls Less Bears is -43.2—one of the lowest in its history. The institutional Bull/Bear Ratio is less than 1.0—an “excessive fear” reading. And, finally, the VIX Volatility Index® is currently at a relatively high 32.45 while the CBOE Put/Call Ratio is 1.02—the highest since March 2020. Those measures do not guarantee the lows are in, but they do imply we are probably getting close.

Finally, stock market valuations are very reasonable. At about 17x trailing EPS, the S&P 500 P/E multiple is now lower than about 70% of the time since 1990. Only during the immediate aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis did it sustain at a level much below 17x. For example, since 1990, the S&P 500 P/E multiple has been less than 15x EPS only 10.5% of the time. Therefore, the downside risk for valuations now appears quite modest while the upside potential is attractive.

Final Comments

Although the Fed is seemingly on a war path—desperately trying to imitate Paul Volcker—and the risk of a recessionary outcome is growing daily, stock investors may want to fight the urge to entirely run away from the stock market.

The lows may not yet be in, but they are probably close. The stock market has been declining all year and is already off by about 25%, which discounts a lot of potentially bad outcomes. Nervous investors have had several opportunities to exit stocks this year—how many sellers could there still be? Inflation has peaked and is decelerating, which should become more and more obvious in the months ahead.

There are a number of unconventional buffers protecting investors against a prolonged and deep recession, including strong private-sector balance sheets, a pristine banking industry, substantial untapped liquidity and savings, Main Street confidence that could improve as a recession unfolds, and continued supply-side recovery to help offset any further demand destruction. Pessimism and fear are already very evident on Wall Street, and the S&P 500 is cheaper than 70% of the time since 1990.

Sincerely,

Vaughn L. Woods, CFP, MBA

Vaughn Woods Financial Group, Inc.

2226 Avenida De La Playa

La Jolla, CA 92037

858-454-6900

Investors should be aware that there are risks inherent in all investments such as fluctuations in investment principal. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Asset allocation cannot assure a profit nor protect against loss. Although the information has been gathered from sources believed to be reliable, it cannot be guaranteed. Views expressed in this newsletter are those of Vaughn Woods and Vaughn Woods Financial Group and may not reflect the views of Bolton Global Capital or Bolton Global Asset Management. The information provided is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered an individualized recommendation or personalized investment advice. VW1/VWA0278.

Leuthold Group